IPMs and the Year Books: Radcliffe v. Dynelay, 1424.

Posted by: mholford 10 years, 3 months ago

Year Books are late-medieval collections of law reports, dating from the 13th century to 1535. They are a treasure trove for legal historians, providing valuable insights into the development of English law in the late medieval period. They are often disappointing for historians from other disciplines, however, as they seldom identify the individuals or places involved the cases they report, instead describing them generically: ‘an heir', ‘a widow', ‘John T, lord of a manor‘. This reflects their purpose; they were produced to record the legal principles established by the cases and included background facts only so far as necessary to understand those principles.[1. J.H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History, 3rd edn (London, 1990), 204-7. For a detailed description, K. Topulos, ‘A common lawyer's bookshelf recreated: an annotated bibliography of a collection of sixteenth-century English law books', 84 Law Library Journal (1992), 641-86.] Yet IPMs can sometimes be used to identify the individuals and properties mentioned in these anonymous Year Book reports. This is one such case, the report of a 1424 hearing in the Exchequer Chamber which can be greatly amplified by reference to two Proofs of Age, CIPM xxii.356 and 365, and nine other IPMs.[2. CIPM xii.134 and 339; xx.675-9; xxii.21-2.]

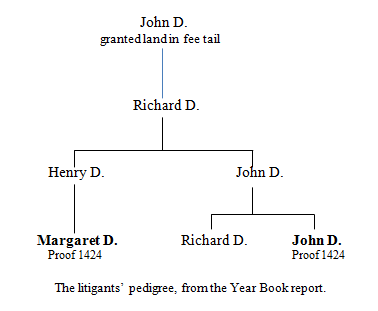

The Year Book for 2 Henry VI (1423-4) contains a report of a suit between Margaret, daughter of Henry D, and her cousin John D relating to unidentified land in the duchy of Lancaster.[3. 2. Year Books, Hil. 2 Hen. VI, f. 5, pl. 2; for analysis and commentary on the report, with a link to the original 1679-80 Vulgate text, see Seipp's Abridgement: http://www.bu.edu/phpbin/lawyearbooks/display.php?id=16828] The report begins with a recital of the facts, which, translated from the original French (and with some abbreviation and paraphrase), reads as follows:

- Henry, duke of Lancaster, gave land that was parcel of his Duchy to one John D. in tail. It descended in tail to his son Richard, and then to Richard's son Henry. When Henry died his bastard daughter Margaret was within age, so duke Henry entered the land and granted her wardship to a stranger. Henry D.'s brother John then entered and deforced the guardian, after which Margaret entered, whereupon John brought an assize of mort d'ancestor against her. He claimed that Margaret was a bastard, making him, John, the next heir in tail, and the Assize found in his favour, and the king pardoned him for his entry. Then by a mandamus it was found that Margaret was heir to her father Henry. John then died leaving two sons, Richard the elder and John the younger, and a diem clausit extremum was issued, but was void because it was addressed to the duke of the duchy of Lancaster or his lieutenant and did not specify a name. Another writ was issued, by which it was found that John held the land of the King, and that Richard was the next heir to John his father, and the king seised him. Richard then died while still within age and without an heir of his body, upon which a devenerunt was issued, by which it was found that his brother, another John, was his next heir, on which the king seised John. Then Margaret and John came to their full ages, proved their ages, and both came into Chancery, and each separately prayed livery of the land from the king's hand.

The Year Book then sets out the judges' several opinions at some length. Some argued that Margaret should have livery because she had been found to be the heir by mandamus, and her heirship had been previously recognised when the king took her lands and wardship into his hand and granted them out. Others argued that John should have livery because it had been found by the assize that Margery was a bastard, and so incapable of inheriting. They could not agree and the matter was adjourned for further consideration. The final verdict is unknown.

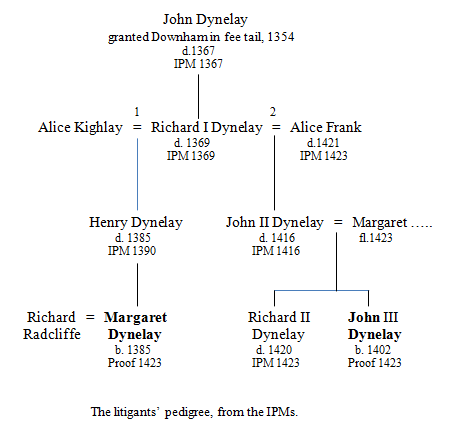

For historians of every persuasion except legal the recital of the background facts is immensely frustrating. It offers a detailed account of several generations of a gentry family and its internal feud over a landholding, but omits the essential basic facts of identity which would make this information useful. Dates are also in short supply, making even the one individual given a full name - Henry, duke of Lancaster - difficult to identify with certainty. However a glance in the index to CIPM xxii under D quickly produces two likely Proofs of Age from 1424: one for Margaret, daughter of Henry Dynelay, the other for John, brother of Richard and son of John Dynelay - CIPM xxii.365 and 356. Other correspondences between the Year Book report and IPMs in earlier CIPM volumes soon confirm that the case did indeed involve the Dynelay family and related to their manor of Downham in north east Lancashire (in the Ribble valley above Clitheroe, on the northern flank of Pendle Hill in the Pennines). With the assistance of these IPMs the story can be re-told in greater detail.

Henry, duke of Lancaster, gave land that was parcel of his Duchy to one John D. in tail.

The IPMs reveal that the original grant in tail had been made seventy years previously, in 1354, by Henry of Grosmont, the first duke of Lancaster - CIPM xx.679.[4. See also E. Baines, History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster, J. Croston ed., i (London, 1888), 150. The version of the Year Book report in Statham's Abridgements, which names the grantor as the duke of Gloucester, is clearly wrong; N. Statham, Abridgement of Cases to the End of Henry VI (Rouen, 1490), f. 120r.]

It descended in tail to his son Richard, and then to Richard's son Henry.

The original grantee, John I Dynelay, died in 1367 and was succeeded by his son Richard I Dynelay (d. 1369) and then his grandson Henry Dynelay (d. 1385) - their IPMs are CIPM xii.134 and 339 and xx.676 respectively.

When Henry died his bastard daughter Margaret was within age, so duke Henry entered the land and granted her wardship to a stranger.

Henry in fact died without issue, but his widow was pregnant and seven months later gave birth to a daughter, Margaret. This inheritance by a posthumously born baby was to trigger a forty-year struggle for Downham between Margaret and her guardians and eventual husband on one side, and her uncle John II Dynelay (Henry's half-brother) and his children on the other. It seems Margaret was initially recognised as Henry's heir. In January 1386 the crown (not ‘duke Henry') granted her marriage and the custody of her lands during her minority to one John Parker of Foulridge (the ‘stranger' mentioned in the Year Book).[5. CFR 1383-1391, 130.]

Henry D.'s brother John then entered and deforced the guardian, after which Margaret entered, whereupon John brought an assize of mort d'ancestor against her. He claimed that Margaret was a bastard, making him, John, the next heir in tail, and the Assize found in his favour, and the king pardoned him for his entry.

The IPMs say nothing of these events (including the allegation of Margaret's bastardy), except for a statement that the guardian, John Parker, was in occupation until about 1391-2. It is not clear when the entry and counter-entry took place, or when John finally obtained possession, but his assize was still proceeding, slowly, in 1394-6 and he paid his feudal relief in 1412, so it must have been between those dates.[6. CIPM xx.675, 678; CCR 1392-6, 304, 352-3; VCH Lancashire vi (1911), 553.]

By July 1394 custody of Margaret, and possibly also of her lands, had passed somehow to William Radcliffe of Todmorden, who in late 1395 or 1396 married Margaret, then aged about 10 or 11, to his son Richard. Over the next thirty years the Radcliffes would make repeated attempts to recover Downham from John II and his heirs.

Then by a mandamus it was found that Margaret was heir to her father Henry.

A writ of d.c.e. had been issued in 1385.[7. CFR 1383-1391, 99; E. Baines, History of the County Palatine and Duchy of Lancaster, J. Croston ed., i (London, 1888), 164.] but no IPM is now extant, and it may be that none was ever produced, because a writ of mandamus was issued in 1390. This was probably not the mandamus referred to in the Year Book, as the resulting IPM, CIPM xx.676, made no mention of Margaret at all, declaring instead that Henry had died without issue and John II was his heir.[8. The calendar entry in CIPM xx.676 is incomplete as the original document is now partly galled - for a fuller version, made in the 17th century before it had faded, see Abstracts of Inquisitions Post Mortem made by Christopher Towneley and Roger Dodsworth. Vol. 1, 1423-1637, ed. W. Langton, Chetham Society 95 (1875), 40-42.] It seems likely that this mandamus was procured by Margaret's uncle John II Dynelay, perhaps as a preparatory step before bringing his assize of mort d'ancestor. A second mandamus which did result in a finding that Margaret was the heir was not issued until after John II's death (the Year Book was wrong to reverse the order of those two events).

John then died leaving two sons, Richard the elder and John the younger, and a diem clausit extremum was issued, but was void because it was addressed to the duke of the duchy of Lancaster or his lieutenant and did not specify a name. Another writ was issued, by which it was found that John held the land of the King, and that Richard was the next heir to John his father, and the king seised him.

When John II died on 6 April 1416 the Radcliffes reignited the struggle over the manor. Within a month a flurry of writs had been issued, triggering no less than three IPMs. Two writs d.c.e. produced CIPM xx.675, which enquired into John II's lands and heirs; a writ mandamus and a commission produced CIPM xx.676 and 677, which enquired again into the lands and heirs of the now long-dead Henry. John II's IPM found his heir to be his son Richard II, a minor aged 15, but Henry's two IPMs declared Margaret to be his posthumous daughter and heir to Downham. The writ and commission for Henry's IPMs had presumably been procured by Margaret and her husband in the hope that they would establish her title to the manor - interestingly they were dated the day before and the same day as John II's death, and predate the writs for John's own IPM by a few days, suggesting that Margaret and Richard had been waiting poised to strike as soon as John II was certainly dying. The commission may have been procured in addition to the writ because it was feared that the escheator's inquest would favour John II (in fact it did not) - the commissioners were doubtless hand-picked to ensure the right outcome, which might explain why three of their jury bore the surname Radcliffe. John II's IPM seems to have prevailed with the authorities in London, however, as in May and June 1416 his son Richard's marriage and custody of Downham were granted to Henry Hoghton, knight, and his widow was assigned dower.

The reference in the Year Book to a writ being void because it was improperly addressed to the duke of Lancaster is puzzling, as there is no evidence of this in the Chancery IPM files. In the early fifteenth century when an IPM was required from Lancashire the practice was to issue two parallel writs, one to the chancellor of the duchy or county palatine of Lancaster and the other, often dated a few days later, to the king's escheator in the county.[9. For examples, see xx.675 or xxii.21, 22.] The former was usually addressed to the chancellor, without naming him, and not to the duke (because since 1399 the duke and the king had been one and the same - he could not send a writ to himself). The 1416 writs d.c.e. for John II's IPM were addressed to the chancellor and the escheator in the correct form, and are unlikely to have been replacements for an earlier incorrectly-drawn writ since they were issued just four days after John's death, hardly long enough for a previous writ to have been issued and then be discovered to be erroneous.[10. CFR 1383-91, 99; xx.675.] In the 1380s and 1390s, however, when the king and the duke had not been the same man, writs were addressed to ‘the duke (by his name and title) or his chancellor in the duchy', or sometimes ‘his lieutenant in the duchy'.[11. Before the union of the duchy and the crown most Lancashire IPMs were begun by ducal writs issued by the palatine chancery in Lancaster to the duke's escheator, but a number were initiated by royal writs from the Chancery in London, addressed to the duke or his chancellor/lieutenant (without a duplicate writ to the king's escheator - the royal writ triggered a local writ to the duke's escheator): for examples of royal writs from the 1380s and 1390s, see xv.811, 859, 973, xvi. 81, 351, 546, 596, 727, xvii.167, 173, 267-8, 1177, 1306. For a recent survey of the legal independence conferred by the county's palatine status, see G.S. McBain, ‘Time to Abolish the Duchy of Lancaster' Review of European Studies 5, no. 4 (2013), 172-93; for more detailed discussion see the authorities mentioned in notes 83-99.] This is exactly the form mentioned in the Year Book, so it seems likely that it was the original 1385 writ for Henry Dynelay which was void for not specifying a name (the writ itself is not extant so we cannot check) - this might explain why the writ is known only from the record of its issue in the Fine Rolls and seems not to have left a consequent IPM.

The following year, 1417, four writs of certiorari were sent to Lancashire requesting details of two records from 1385: the IPM which ought to have been held on Henry's death, and an assize successfully brought in the name of his infant heir Margaret for possession of 40a. in Downham. A copy of the assize was duly returned, but not of the IPM; instead the 1390 IPM was sent - CIPM xx.676, 679. Again, these writs were presumably procured by Margaret and her husband Richard Radcliffe in order to gather evidence for their struggle - the 1385 assize was certainly favourable to their case. They do not seem to have resulted in recovery of the manor, however.[12. Two of the writs in C 138/24/58 have been allocated to the wrong IPMs in CIPM xx; m. 2 ought to be in xx.678, not 676, and m.11 in 676, not 678.]

Richard then died while still within age and without an heir of his body, upon which a devenerunt was issued, by which it was found that his brother, another John, was his next heir, on which the king seised John.

Richard II died in 1420, still a minor, and the following year so also did his grandmother Alice, Richard I's widow, who had enjoyed dower in one third of Downham for over half a century.[11. Her dower was assigned in CIPM xiii.102] It was not until May and June 1423, however, that writs mandamus were issued in respect of Alice and writs devenerunt in respect of Richard II. The resulting IPMs, both held on 25 June with the same jury, declared the heir to be Richard's brother John III - CIPM xxii.21, 22.

Then Margaret and John came to their full ages, proved their ages, and both came into Chancery, and each separately prayed livery of the land from the king's hand.

John III had been a minor when his brother and grandmother died, but was just a few days over 21 by the time their IPMs were taken. However it was not until a year later, on 12 July 1424, that a writ de etate probanda was issued for him. On the very same day another was issued for his cousin Margaret, then aged 38 (not just recently come of age, as the Year Book implied). The two resulting proofs were taken on different dates (12th and 18th August 1424) by different juries in different places, but it cannot be a coincidence that the writs had been issued simultaneously. The Radcliffes must have launched yet another attempt to recover the manor, presumably commencing the lawsuit recorded in the Year Book.[13. No record of the suit has been found, but the Year Book tells us that it was in Chancery (and in February 1424 John III gave an undertaking in Chancery to appear at the next Lancaster assizes to give security for keeping the peace toward William Radclyf esquire; CCR 1422-9, 141). The hearing recorded in the Year Book was in the Exchequer Chamber, however. At this time it was the practice to refer difficult questions of law arising in the common law courts or in Chancery to an assembly of all the justices, usually held in this location. These ‘hearings in the Exchequer Chamber' had no legal authority, but the considered opinions of the assembled judges were seldom ignored and they operated as an unofficial supreme court. That this particular hearing was presided over by the Chancellor may reflect its origin in his court.] The proofs may have been agreed or ordered to be taken in connection with those proceedings.

The outcome of the lawsuit is not recorded in the Year Book, and is not revealed by the IPMs either. Evidence for the ownership of Downham in subsequent decades is sparse, but what little there is suggests the Dynelays won - certainly later in the century the manor was in the hands of individuals of that surname.[14. VCH Lancs vi (1911), 553.]

Both families, the Dynelays of Downham and Radcliffes of Todmorden, seem to have been minor gentry, holding little more than a single manor each, at best.[15. On the evidence of the IPMs, the Dynelays held nothing but Downham itself plus some lands in Clitheroe, while the Radcliffes do not feature in any IPM at all, of either the royal administration or the duchy. For an idea of the Radcliffes' early fifteenth-century landholdings, which seem to have been sub-manorial, see VCH Lancs v (1911), 229, n. 68.] Since that manor was Downham it is small wonder they fought so tenaciously over it - the real wonder is that they could afford to do it. Their 40-year struggle, fought partly in the courts of Lancaster but so often also in London, must have been ruinously expensive. One wonders whether they were each backed by more powerful interests, supporting the Downham disputants as proxies through whom to pursue a larger feud.[16. Some hint of the Radcliffes' connections can be found in VCH Lancs v (1911), 229, n. 68; for instance, in 1400 William Radcliffe of Todmorden, presumably Richard's father, had been granted an annuity of £10 by Henry IV.]

Their frequent resorts to the royal Chancery in Westminster rather than the local palatine chancery in Lancaster (which had primary jurisdiction for the issue of writs and conduct of lawsuits originating within the county)[17. See n. 11.] might be seen as attempts to circumvent an opponent's local influence by appealing to a more disinterested royal administration, or perhaps to counter it with the influence of one's own friends in London. However it is odd that this seems often to have been done by both sides simultaneously - in 1416 and 1417, for example. Moreover it is noteworthy that from as early as 1367 (when John I Dynelay died, two generations before the Radcliffe-Dynelay dispute even began) every major IPM relating to the Dynelay family originated with a Westminster writ. There is still more work to be done on teasing out the local background to the dispute, both as to the two families' connections to locally competing affinities and the exact interrelationship between the overlapping jurisdictions of the royal and palatine chanceries in Lancashire.

Downham lies in the Ribble valley on the north flank of Pendle Hill, seen here. (Photo: Thomas Saunders)

Downham lies in the Ribble valley on the north flank of Pendle Hill, seen here. (Photo: Thomas Saunders)

Even without the full story, the struggle between the Radcliffes and the Dynelays is fascinating on several levels. First, it provides a good example of how the Year Books and IPMs can amplify and supplement, and occasionally correct, each other. Admittedly the process is mostly one way, the IPMs putting the flesh back on the otherwise skeletal narrative in the Year Book. Here the IPMs have not only identified the property and the disputants (thus permitting the case to be known for the first time by its proper title, Radcliffe v. Dynelay), but has also furnished much extra detail about the seventy years of back-history which lay behind the 1424 hearing. However, the Year Book has also provided a few details unobtainable from the IPMs, notably that John II's assize of mort d'ancestor had found Margaret to have been illegitimate, and the reference to the drafting defect which voided a writ of d.c.e.

For social and economic historians Radcliffe v. Dynelay is perhaps most interesting as an example of the use of IPMs as weapons in the land wars waged by the late medieval gentry and nobility. We tend to think of the IPMs purely as a top-down administrative system for enforcement of the crown's feudal prerogatives, but, as this case shows, the system was also exploited enthusiastically by the gentry for their own purposes. We see here the aggressive use (or misuse) of IPM writs to further disputes over inheritance, notably the repeated inquisitions on Henry Dynelay. No doubt each was accompanied by attempts at jury-tampering and other abuses of process in an effort to ensure the right result (placing three Radcliffes on the jury of one of the 1416 inquisitions, for instance). It is likely that these IPMs were intended to provide evidence for subsequent lawsuits; thus the 1390 mandamus for Henry Dynelay was probably preparatory to the assize of mort d'ancestor brought by John II Dynelay a year or two later. The Radcliffes also used IPM writs of certiorari to collect evidence - copies of earlier IPMs and even of judgements in lawsuits. Even the writ de etate probanda could be pressed into service for this purpose. In 1424 it was hardly necessary to prove that Margaret Radcliffe was of age (she was then 38), and the real purpose of her Proof was presumably to provide disproof of the allegation that she was a bastard.[18. Eleanor Roos' second Proof of Age, held when she was 66, is no doubt another example, as discussed in an earlier Featured Inquisition.]

Radcliffe v. Dynelay also casts an interesting light on the quasi-judicial nature of IPMs. To modern eyes IPMs appear to be mere administrative procedures, exercises in information gathering by the crown's financial apparatus, not dissimilar to a modern tax return. In contemporary eyes they were more than this, however. Because they were verdicts of juries summoned by a royal writ they were also in some degree judicial proceedings whose outcomes could not easily be put aside. In Radcliffe v. Dynelay at least two of the country's senior judges argued that the verdict of an IPM jury as to the heir could not be defeated by a contrary judgement of the palatinate court of Chancery (though they were also influenced by the fact that on the strength of the IPM the king had subsequently made a grant of the heir's wardship). It may be, however, that only IPMs held pursuant to a royal writ, virtute brevis domini regis, were regarded in this light. Ex officio IPMs, which were held pursuant merely to the power inherent in the office of escheator, may have lacked this status, and so were accorded less importance.[19. See, for example, comments in Skrene's case, Pasch. 14 Edw IV, pl. 4; and in Bogo de Knoville's case, Mich. 4 Edw II, pl. 27. The latter appears in translation in Year Books of Edward II, iv, 3 & 4 Edward II (1309-1311), F.W. Maitland and G.J. Turner eds., 22 Selden Society (London, 1907), 115-123.] It was this judicial authority which made an IPM so powerful a weapon in the land wars, and explains why the three deaths of Henry, John II and Richard II Dynelay between them called forth more than a dozen writs of d.c.e., mandamus, certiorari and de etate probanda.[20. Counting duplicate writs to the palatine chancellor and the escheator as one.]